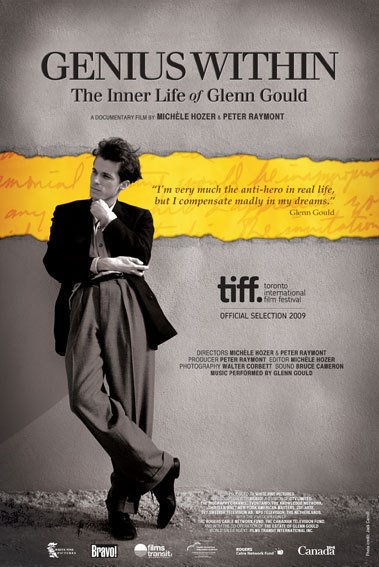

Today was about documentaries. The first in the main auditorium was the much anticipated Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould (Canada 2009). There have been several previous Glenn Gould films, including the celebrated Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993), but I haven’t seen any of them, so I can’t make comparisons, but I would be surprised if many are better than this one. I enjoyed every minute of the 108.

Today was about documentaries. The first in the main auditorium was the much anticipated Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould (Canada 2009). There have been several previous Glenn Gould films, including the celebrated Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993), but I haven’t seen any of them, so I can’t make comparisons, but I would be surprised if many are better than this one. I enjoyed every minute of the 108.

For the uninitiated, Glenn Gould (1932-82) was an eccentric but highly talented and driven pianist. I’m something of a philistine about classical music but I knew of Gould as a major figure in Canadian culture and I was fascinated to learn about his career – filling in the many gaps in my knowledge. Unlike yesterday’s The Miracle of Leipzig which struggled with the lack of archive material, no such problems faced the Canadian duo Michèle Hozer and Peter Raymont who made this film. Much of Gould’s life as a middle-class kid from the Toronto suburbs was documented by friends and family and he himself preferred to deal with media representations than to perform ‘live’ in front of audiences (he stopped performing at the height of his concert career in his early 30s). But although the ‘personal’ stuff is very interesting, I was riveted by two events that were recorded ‘officially’ – Gould’s tour of the Soviet Union in 1957 when he was just 24 and his first recording stint at Columbia in New York in 1955 when he had the youthful arrogance to record the Goldberg Variations for the first time. The Russian footage is amazing and we learn that Gould’s first concert was only half full at the start, but the audience were so amazed at his technique and feel for Bach (not officially ‘approved’ in the Soviet Union) that they all dashed out to telephone friends. The second half of the evening performance was full and the rest of the tour was a sell-out.

Because of the wealth of material, the film could be composed entirely from archive and witness interviews. No voiceover commentary was necessary and the editing is seamless in stitching the story together using the interviews and Gould’s own recordings. It’s becoming something of a cliché for me, but I really enjoy the ‘Canadianness’ of people like Glenn Gould who returned to Toronto because he identified with the city. The Columbia head honcho in New York is quite insulting about Gould’s ‘provincialism’ but he is ignored. I can’t recommend this film highly enough. It seems to have deals with dozens of documentary TV channels, so you’ll probably have the chance to see it on the box. It has been released to US cinemas so I hope someone picks it up for international sales. I’m sure it would be enjoyed by many audiences on the big screen.

Because of the wealth of material, the film could be composed entirely from archive and witness interviews. No voiceover commentary was necessary and the editing is seamless in stitching the story together using the interviews and Gould’s own recordings. It’s becoming something of a cliché for me, but I really enjoy the ‘Canadianness’ of people like Glenn Gould who returned to Toronto because he identified with the city. The Columbia head honcho in New York is quite insulting about Gould’s ‘provincialism’ but he is ignored. I can’t recommend this film highly enough. It seems to have deals with dozens of documentary TV channels, so you’ll probably have the chance to see it on the box. It has been released to US cinemas so I hope someone picks it up for international sales. I’m sure it would be enjoyed by many audiences on the big screen.

Next up was a German doc about a Lebanese family struggling with immigration rules in Berlin. Neukölln Unlimited (Germany 2010) was screened in the Queen’s Theatre in Emmanuel College – an impressive lecture theatre in a new building, but hard on the backside for a 90 minute movie. Fortunately it was an entertaining film, directed by Agostino Imondi and Dietmar Ratsch. The i website (in English) is here. Imondi is a Swiss-born director trained in Rome.

Neukölln is a district of Berlin which is presumably not that different to parts of London in attracting refugees and asylum seekers. The family in this ‘social documentary’ are Lebanese Shiites. The parents fled persecution during the Lebanese Civil Wars, but all the children have been born and brought up in Germany. They don’t speak Arabic and after being deported once, the family came back (almost immediately, I think. The parents are now divorced and the older (teenage) children all have guaranteed residency for the next year or so because they are in school or apprenticeships. The mother and her youngest child (a baby) still face deportation and the order seems to depend on the possibility that the children, 18 year-old Hassan, 19 year-old Lial and 15 year-old Maradona can earn enough to match the welfare payments made to mother and baby. I confess that the German bureaucracy baffles me but I suspect it is no better (and no worse) than the equivalent gobbledygook in the UK. On this score, however, I did note that a young black woman said that at least in England/London (she had a British passport) there were more black people and she didn’t get called an ‘African’.

The children’s chance of earning the cash is boosted by their prowess in performance skills (possibly a ‘non-pc’ attribute in the UK where linking an ethnic minority to dance skills is a bit ‘iffy’). Hassan is a skilled street dance/hip-hop star who performs in a group at a Berlin theatre in his spare moments and Maradona is a breakdance star. Lial works in a venue promoting boxing matches and other entertainment. Hassan has the most responsibility (and a girlfriend) but Lial is equally committed to helping the family. There is a short sequence, which I would have liked to see extended , in which she discusses the changing family environment for Muslims depending on where they are and how they are brought up – certainly, as far as I can see, Hassan respected her position. Maradona is the bad boy who gets into trouble at school, risking deportation because of a criminal record – but he’s hard to dislike. Everything ends not ‘happily’ but certainly ‘hopefully’. I must also reference the true moment of global culture when Hassan and Maradona travel to Paris to take part in a streetdance contest/exhibition and a discussion takes place, in English, between French and German Arabs about how they are treated in their ‘home’ countries (i.e. in Europe). I’m not sure I totally followed the discussion (I blame the seats) but this seemed important. As well as the performance element (we see several dance performances) the film also utilises animation to record the family history of flight from conflict.

Finally, in the same venue, I watched an American documentarist’s essay about the Zabbaleen – the Coptic Christian garbage collectors of Cairo – in Garbage Dreams (US 2009). This was also a ‘social documentary’, focusing on a wider range of characters, but picking out an educated woman who set up a ‘Recycling School’ and three teenage boys who represent the next generation of garbage collectors. The filmmaker Mai Iskander acknowledges her major influence as the Maysles Brothers, important members of the Direct Cinema movement during the 1960s and 1970s (though she describes the approach as ciné verité – which to me means something slightly different). She has worked elsewhere in Africa as well as in the commercial industry. Garbage Dreams was a long-term commitment (over several years) that has also been followed up on US public television (see this PBS website). There is also an official website for the film.

The film is true to the Direct Cinema legacy, driven forward by its four principals. Laila is the woman who opens the ‘Recycling School’ (which teaches “map-reading and computers”) and attempts to organise the community and act as some kind of mentor for the four young men. She also provides the tetanus shots that are used to protect the workers handling the waste from Cairo’s households and attempting to recycle it. Nabil, a beautiful strong young man is relatively passive. Adham is more entrepreneurial but has to grow up fast when his father is imprisoned and Osama is something of a fantasist unable to hold down a job for very long. Through these individuals and their families we learn about the Zabbaleen and their business. They routinely recycle around 80% of the waste that they collect, turning it into raw materials that can be exported. When Adham and Nabil are able to join an exchange programme and travel to South Wales, they are impressed by new technologies in waste recycling – but not by UK recycling rates – and by the local residents’ co-operation in sorting the waste. Returning to Cairo they hope to develop this home-sorting of waste with their customers, but Cairo (a city of 18 million with no properly organised municipal waste collection/disposal service) now has two or three large European companies contracted to deal with the problem. These companies seemingly don’t care that much about recycling and they won’t co-operate (although they do recruit workers locally). Gradually the Zabbaleen are losing the business. But there is some hope at the end of the film and the ‘project’ continues (hence the websites).

I found the film to be both uplifting in human terms and expertly made with real community involvement. The only slight drawback is that this kind of documentary can only offer us the chance to see what a small group experiences in their work and home lives. We have no idea about how the rest of the community (there are 70,000 Zabbaleen) is doing or how the Cairo authorities are planning to deal with the problem (or not). Having said that, a quality film that promotes recycling and involves those working at the sharp end is always going to be worthwhile.